By Laura Morales

Introduction

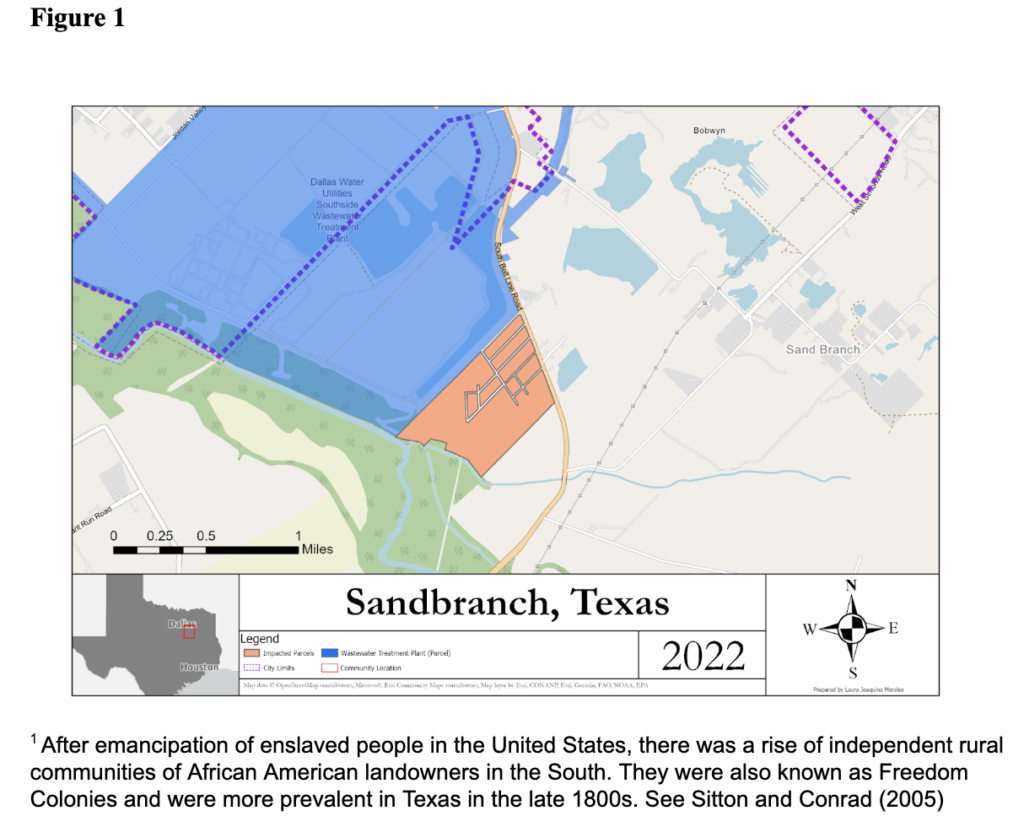

In 2017, an article published by the Guardian titled “America’s dirty little secret’: the Texas town that has been without running water for decades” highlighted a historical Freedman1 settlement, Sandbranch, which is located 15 miles from downtown Dallas, Texas. Sandbranch, an unincorporated community, does not have any municipal services which include potable water. A town on the urban fringe of one of America’s wealthiest cities, prompts the question for this memorandum: when water and sewer service are not available, what are the options to help acquisition or incorporate households into a municipal service? In addition, how does this relate to planning and why is it important? Throughout this memorandum, relevant traditional economic and policy theories are introduced in combination with environmental justice literature to ascertain a systematic review of the condition of Sandbranch. Short, intermediate, and long term feasible solutions are presented. Short term solutions include a university-partnership for stability of public interest and long term water management is examined. Utilization of the Clean Water State Revolving Funds made available through the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act (2021) serves as a potential opportunity to build necessary infrastructure.

Water Insecurity Defined & Water Gap

Water insecurity has been measured by assessing indicators of water availability or quality (Cook and Bakker, 2012; Garrick and Hall, 2014). However, in more recent years water insecurity has been defined as inadequate, unreliable, insufficient and unaffordable (Wutich et al 2017). The difference in definition would be the scale of the study which could range from a country wide perspective to a community based framing (Cook and Bakker, 2012). Within the United States, approximately 1.1 million people lacked piped water access between 2013 and 2017 (Meehan et al, 2020). The gap in universal access to water in high income countries has been viewed through four main factors (Meehan et al., 2020). First being the difference in coverage of utility districts and municipal boundaries would result in exclusion of the network (Pierce et al, 2019; Meehan et al 2020). Additionally, the disproportionate geography of housing connected to racialized wealth gaps also produce water insecurity (Meehan et al. 2020). An example of this would be residents of mobile homes and trailer parks suffering from water insecurity due to neglected infrastructure maintenance or lack of reliability in their network (Pierce and Jimenez, 2015; Pierce and Gonzalez, 2017). Furthermore, citizenship status could be a predictor of water insecurity. The inability to vote in regional water governance institutions could restrict access to water access within Hispanic communities (Jepson, 2012). Lastly, the lack of planning for infrastructure or policy frameworks perpetuate marginalization through the institutionalization of existing structures (Meehan et. al, 2020).

Analysis

An opinion article in the Dallas Morning News, the author states “the county has done just about all it can do, and residents have made a choice to stay on property that has been passed on for generations” (DMN, 2019). Traditional economic theories are invoked by this statement and are described through Tiebout’s model on residential sorting and Coasian Bargaining which are ultimately limited and expose environmental justice concerns.

Economic Theory

Tiebout (1956) suggested that people “vote with their feet” meaning that local governments embed choice and competition into the provision of public goods. Although this is less desirable for equity reasons when wealthier children are segregated from poorer children via school districts, advocates of this model emphasize benefits of local diversity which would enable a person to live in a place that serves their own needs (Glaeser, 2011). From environmental justice literature, initial sorting by income will result in poorer households being in more polluted areas (Banzhaf et al, 2019). However, if pollution is not already in the area industrial facilities will locate those areas because of their willingness to pay for specific locations. Coase Theorem (1960) states that under well defined property rights and zero transaction costs, market transactions will ensure efficient use of resources. Coasean gives potential for transactions on two-sides because households may have a tolerance for pollution and willingness to accept compensation for the pollution activity (Banzhaf, 2019).

The problem with these economic theories is who is negotiating for the community to ascertain correct compensation and how do people move without appropriate information involved. Within the case of Sandbranch, nonpoint source pollution complicates negotiations because no single actor bears the responsibility of the pollution that contaminated the private wells. Similarly, asymmetric information would distort transaction costs (i.e enforcement fees, court costs, decision making costs) in this situation (Ferraro, 2008). In addition, traditional economic theories point towards governance structures and property rights of the owners. Given the complexity of the situation, there have been local efforts to address the environmental justice concern however there has not been a local public policy created to gain water access. This observation lends itself to look at policy theories on what shapes discourse on community water insecurity that led to the Sandbranch effect.

Policy Theory

Beginning with Downs’(1972) seminal article that presented the issue-attention cycle with regards to environmental policy, the author describes a process in which the public gains and loses interest on a particular issue. There are five stages described: pre-problem stage, alarmed discovery and euphoric enthusiasm, realizing the cost of significant progress, gradual decline of public interest, and post-problem stage (p 40). Downs’ states that problems that are likely to go through a cycle are ones that are suffering as a “numerical minority”, “generated by social arrangements”, and “having exciting qualities” (p. 43). With Sanbranch, there have been 12 printed articles and 11 videos recording the circumstances between 1980 and 2018 (Reynolds, Upshaw, and Larson, 2019). When it comes to the stage of realizing the cost of significant progress, interest declines in accordance with the Downsian model. Using Google Trends, the search term “Sandbranch” is able to be tracked as interest over time from 2004 to 2022 (Figure X). A value of 100 is the peak popularity for the term. A value of 50 means that the term is half as popular. A score of 0 means there was not enough data for this term.

Figure 2

The Downsian model states that a numerical minority is important to frame the issue around but understanding on what sustains interests and enters a solution arena is important. A crucial component that has been echoed throughout this memorandum is race. An interview from Sandbranch recorded a resident stating, “We are too weak, too poor, and too Black for folks to care . . . I believe nothing of what I hear and only half what I see, you hear me?” (DMN, 1985). The nexus of class, race, and environmental remediation costs are likely why the Downsian model cycles. Before discussing solutions, another component to water that contributes to the Sandbranch effect is the legality of water in Texas and how the Federal Emergency Management Agency plays a role.

Legal Context

Texas groundwater law is unique because it regulates the resource through the “rule of capture” (See, Sipriano v. Great Spring Waters of America, Inc., 1 S.W.3d 75, 76 (1999)). This means that property owners do not need permission or permit to drill wells or pump water because they have the right to all water underneath their land (Linnetz, 2021). There is a considerable focus on regulating groundwater locally which also means that there is no agency in place that governs all of Texas groundwater (Linnetz, 2021). Groundwater has legal structure similarities to oil and gas but continues to be regulated in a fragmented way unlike oil and gas which is highly centralized (Linnetz, 2021). This is an important aspect because if groundwater becomes contaminated there are very few resources to assist with abatement. Currently there are locally governed districts for management in groundwater but Dallas County in which Sandbranch is located does not have a district.

According to a news article, an additional barrier Sandbranch has encountered was its physical location within a floodplain which FEMA engaged in buyouts of property in accordance with Dallas County (Savali, 2016). Within academic literature, buyouts of private property are common flood management policy (Siders, 2019). However, buy-outs within counties are likely to be located in “relatively poorer, less densely populated areas, with lower levels of education, lower English proficiency, and greater racial diversity” (Mach et al, 2019). In addition, flood hazard mitigation may be available to the more privileged due to local-level political pressures (Mach et al, 2019; Munoz and Tate, 2016). These buyouts lead to further inquiry into equity which prompts this memorandum to discuss solutions to the Sandbranch effect.

Potential Solutions

Throughout the analysis section, relevant economic and policy theories with legal considerations were described through a lens of community water insecurity to fully understand the context in which left Sandbranch without water. Beginning with the Downsian model, building long standing attention to the Sandbranch effect could be best done via a university-county partnership. Currently, Texas Women’s University Nursing has been serving Sandbranch by providing wellness checks. Texas A&M University School of Law students have completed a legal research paper outlining legal requirements to sell fresh produce and eggs (NRS, 2019). A complement to this assistance would be the involvement of a public affairs program. Two major public affairs master’s programs exist at local universities which are The University of Texas at Dallas and University of North Texas. These institutions would be ideal because of proximity to Sandbranch and local knowledge of policies and politics. A public affairs program would be suitable because there is typically a capstone course where students tackle practical problems and coordinate with local public managers to create a report.

Many of these students will graduate and take on roles in local and state government which channel a pipeline of interest. In addition, given the complexity of this issue such as the natural resources or policy component students could further elaborate on direction regarding the fragmented system. The county would be the client because Sandbranch’s status of unincorporated but trips to interview actual residents and see the conditions would be necessary. The capstone project might benefit from drawing others from different disciplines to participate to gauge feasibility of more long term solutions.

Intermediate Solution

An intermediate step would apply to the Drinking Water and Clean Water State Revolving Funds (CWSRF) established by the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act (2021). This act expands opportunities to provide funding for disadvantaged communities specifically for decentralized wastewater systems and groundwater protection (CWSRF Factsheets, 2021). Determining eligibility should be a priority but given the limitation of funds there should be a plan for continued maintenance cost.

Given the fragmented nature of groundwater, a suggested effort would be the establishment of a private well grant at the county level. Dallas County is not part of a district groundwater program, but could voluntarily help establish a well compensation program similar to the Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources model to prevent future contamination and still locally manage groundwater. Wisconsin’s program was established through law, which would make this suggestion reliant on voluntary assistance although it would be considered a CWSRF eligible project.

Long Term Solutions

Sandbranch has formed a water cooperative in order to provide efficient, effective, and reliable water and wastewater utility services. It is currently governed by a board of five individuals who are property owners in the Sandbranch community (Sandbranch DWSC, 2019). Although they were able to secure a $30,000 USDA Search Grant to produce a preliminary engineering report they have not been able to build the water/wastewater system. If this were achieved, maintenance costs and human resources could be challenging. An example from Finnish water cooperatives may be helpful in determining direction. Water cooperatives can be used as temporary solutions which could then be a stepping stone to municipal water service.

However, if municipality service is not what is desired then looking towards economic development should be considered. The next step to help solve this issue of maintenance cost would be engaging in economic development through policy design to leverage resources and other factors. Sandbranch sits also within rich natural resources such as sand and gravel, native Texas plants, and a Palmetto-Alligator Slough Reserve. The ability to manage and leverage these resources through eco-tourism could increase funding for maintenance of the water and wastewater system. The Dallas Environmental Center is located approximately 4.5 miles from Sandbranch which could be a complimentary feature if eco-tourism were promoted.

Future Environmental Planning for Underserved Communities

There has been a distinct disconnect between the county level future planning and the community of Sandbranch. From a planning perspective, there should be more future involvement with similar communities that are underserved in the county. However, the purpose of this memorandum is to explain how this relates to planning and why it is important for planners. Planners may engage in planning equity in which they are able to promote equitable solutions through the production of long term planning (Krumholz and Forester, 1990). Outside of the administrative capacity, planners may also adhere to the paradigm of Integrated Water Resource Management (IWRM). IWRM is defined as a systems, holistics, or ecosystem approach to water water management (Mitchell, 2005). The usage of IWRM to engage in community water security allows for resiliency in water management and more of an “analytically robust” approach (Cook and Bakker, 2012). Future water planning must engage in a holistic approach using ecological boundaries rather than administrative ones. While water resources (specifically quantity and quality) has been discussed, accessibility to water for consumption should also be incorporated into long range planning specifically in a drought prone state like Texas.

References

Banzhaf, Spencer, Lala Ma, and Christopher Timmins. “Environmental justice: The economics of race, place, and pollution.” Journal of Economic Perspectives 33, no. 1 (2019): 185-208.

Clean Water State Revolving Fund (CWSRF) Factsheets. EPA. Environmental Protection Agency. Accessed March 14, 2022. https://www.epa.gov/cwsrf/clean-water-state-revolving-fund-cwsrf-factsheets.

Coase, R. H. “The Problem of Social Cost.” Journal of Law and Economics 3 (1960): 1-44.

Cook, Christina, and Karen Bakker. “Water security: Debating an emerging paradigm.” Globalenvironmental change 22, no. 1 (2012): 94-102.

Dallas Morning News (2019, June 26) Bringing water to Sandbranch isn’t the answer to helping peoplethere. Retrieved March 3, 2022, from https://www.dallasnews.com/opinion/editorials/2019/07/26/bringing-water-to-sandbranch-isnt-the answer-to-helping-people-there/

Downs, Anthony. “Up and down with ecology: The issue-attention cycle.” The public 28 (1972): 38-50. Garrick, Dustin, and Jim W. Hall. “Water security and society: risks, metrics, and pathways.” AnnualReview of Environment and Resources 39 (2014): 611-639.

Ferraro, Paul J. “Asymmetric information and contract design for payments for environmental services.” Ecological economics 65, no. 4 (2008): 810-821.

Glaeser, Edward L. “Urban Public Finance.” Harvard University (2011).

Jepson, Wendy. “Claiming space, claiming water: Contested legal geographies of water in South Texas.” Annals of the Association of American Geographers 102, no. 3 (2012): 614-631.

Krumholz, Norman, and John Forester. Making equity planning work: Leadership in the public sector. Vol. 43. Temple University Press, 1990.

Linnartz, Kathryn “Texas Groundwater: Balancing Individual Property Rights with a Depleting Natural Resource,” Texas Tech Law Review 53, no. 4 (Summer 2021): 773-808

Mach, Katharine J., Caroline M. Kraan, Miyuki Hino, A. R. Siders, Erica M. Johnston, and Christopher B. Field. “Managed retreat through voluntary buyouts of flood-prone properties.” Science Advances 5, no. 10 (2019): eaax8995.

Meehan, Katie, Jason R. Jurjevich, Nicholas MJW Chun, and Justin Sherrill. “Geographies of insecure water access and the housing–water nexus in US cities.” Proceedings of the National Academy ofSciences 117, no. 46 (2020): 28700-28707.

Meehan, Katie, Wendy Jepson, Leila M. Harris, Amber Wutich, Melissa Beresford, Amanda Fencl, Jonathan London et al. “Exposing the myths of household water insecurity in the global north: A critical review.” Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews: Water 7, no. 6 (2020): e1486.

Mitchell, Bruce. “Integrated water resource management, institutional arrangements, and land-use planning.” Environment and planning A 37, no. 8 (2005): 1335-1352.

Muñoz, Cristina E., and Eric Tate. “Unequal recovery? Federal resource distribution after a Midwest flood disaster.” International journal of environmental research and public health 13, no. 5 (2016): 507. NRS (2019, April 23) AGGIE LAW STUDENTS PURSUE DIGNITY FOR IMPOVERISHED LOCALCOMMUNITY. Retrieved March 14, 2022 from https://blog.law.tamu.edu/nrs/aggie-law-students-pursue-dignity-for-impoverished-local-communit y

Pierce, Gregory, Larry Lai, and J. R. DeShazo. “Identifying and addressing drinking water system sprawl, its consequences, and the opportunity for planners’ intervention: evidence from Los Angeles County.” Journal of Environmental Planning and Management 62, no. 12 (2019): 2080-2100.

Pierce, Gregory, and Silvia Jimenez. “Unreliable water access in US mobile homes: evidence from the American Housing Survey.” Housing Policy Debate 25, no. 4 (2015): 739-753.

Reynolds, Paul D., Janiece Upshaw, and Theodore Larson. “A Qualitative Study of an Environmental Justice Fight in a Freedman Community: A Content Analysis of Sand Branch, Texas.” Journal ofTheoretical & Philosophical Criminology 11, no. 3 (2019): 133-158.

Savali, K. W. (2016, December 14). Sandbranch, Texas: A small community denied water for over 30 years fights back. The Root. Retrieved March 3, 2022, from https://www.theroot.com/sandbranch-texas-a-small-community-denied-water-for-o-1790858153

Sandbranch Development and Water Corporation (Sandbranch DWSC) Retrieved from http://www.sandbranchdwsc.com/

Siders, Anne R. “Social justice implications of US managed retreat buyout programs.” Climatic Change152, no. 2 (2019): 239-257.

Sitton, Thad, and James H. Conrad. Freedom colonies: independent Black Texans in the time of JimCrow. No. 15. University of Texas Press, 2005.

Tiebout, Charles M. “A pure theory of local expenditures.” Journal of political economy 64, no. 5 (1956): 416-424.

The Supreme Court of Texas. Sipriano v. Great Spring Waters of America, 1 SW 3d 75 (Tex. Supreme Court 1999).