Promoting Investment and Innovation in Social Determinants of Health Interventions through State Medicaid Programs

By Noel Martin D. Rubio

Problem – A public goods problem leads to underinvestment in critical social, economic, and environmental supports to health

The social determinants of health (SDoH)—defined by the United States Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) as “conditions in the environments in which people are born, live, learn, work, play, worship, and age that affect a wide range of health, functioning, and quality-of-life outcomes and risks”—account for up to 80% of individuals’ well-being (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services 2020 and Hood et al. 2015). A growing body of global public health research literature demonstrates that investing in innovative interventions that target non-medical social needs at the community level results in better health outcomes for both individuals and entire populations that can be sustained over prolonged periods of time (World Health Organization 2019). In recent years, health systems across the U.S. have made concerted strides toward the systematic adoption of a more holistic approach to delivering health services that explicitly addresses social, economic, and environmental factors with significant influences on health outcomes. However, interventions aimed at bolstering housing stability, food security, air quality, healthy behaviors, and related areas of need face formidable financing, regulatory, and implementation headwinds. Such challenges inhibit the extent and ultimate impact of SDoH interventions on overcoming a long-running vicious cycle whereby vulnerable groups—including racial and ethnic minorities, older and lower-income households, and rural and geographically isolated communities—suffer from poorer health outcomes directly resulting from lack of access to critical social services and enabling environments, which in turn drives these groups’ disproportionate need for non-medical supports to their health in the first place (Boutar et al. 2015).

Nichols and Taylor (2018) hypothesize that SDoH interventions function effectively like public goods, implying that underinvestment in and underprovision of SDoH interventions stem from a free-rider problem. In other words, health system stakeholders are reluctant to invest in social needs supporting their communities’ health because they are unable to efficiently limit the benefits of their investments to just themselves. For example, if a local hospital designs, implements, and finances a care coordination program through an innovative partnership with a community benefit organization to improve housing support services provided to chronically homeless beneficiaries within a specific area, under the status quo, that hospital cannot prevent other health care provider networks in its area from also reaping the cost-effective benefits resulting from its program such as reduced hospital re-admissions associated with an increase in housing security among affected populations. Nichols’ and Taylor’s analysis is predicated on the assumption that health system stakeholders are driven primarily by self-interest, implying that proper governance mechanisms, cross-sector collaboration, multilateral financing streams, and sustainable funding approaches that capitalize on this self-interest and allow stakeholders to calculate and capture returns on their investments are necessary to resolve the free-rider problem exacerbated by fragmented issue networks, regulatory gaps, and an inadequate evidence base (Nichols and Taylor 2018).

Context – Medicaid’s national scope, legal and funding authorities, flexibilities, and potential for innovative partnerships render it a promising platform for delivering needed SDoH interventions at the community level

State Medicaid programs stand out as promising platforms for addressing social needs at the community level because, by design, they combine public funding through various federal and state authorities with private sector health system partnerships; are able to leverage statutory and regulatory provisions that allow for flexibilities in experimenting with SDoH interventions; and serve beneficiaries facing disproportionately greater risks of poor social and health outcomes, such as low-income households, pregnant women, children, and individuals living with disabilities (Manatt Health and Phelps and Phillips, L.L.P. 2020). Among the mechanisms available for state Medicaid programs to leverage in implementing SDoH interventions are amendments to state implementation plans submitted to the federal government, waivers of certain federal requirements in exchange for innovative pilot programs targeting social needs, and managed care instruments through accountable care organizations or similar networks, including “in-lieu-of” and “value-added” services, capitated and value-based payment systems, and robust coordinated care and case management structures (Bachrach et al. 2016).

The state-to-state flexibility inherent in Medicaid has yielded considerable variation in individual states’ and regions’ capacity for and progress toward SDoH innovation. To date, approximately 40 states have incorporated SDoH-addressing activities into their Medicaid program designs through managed care contracts and one type of waiver—known as a Section 1115 demonstration waiver—alone (DeSalvo and Leavitt 2019). Interventions cover a wide range of priorities; across states, the priority areas receiving the most focus include improving health behaviors, addressing housing instability, and bolstering family and social supports (Schwartz 2019). The level of flexibility and differentiation unique to Medicaid facilitates a diverse array of upstream social interventions along these and other SDoH domains, promoting a “pilot-to-scale” model of testing programs in small geographic areas with defined populations, evaluating programmatic successes and shortfalls, adjusting programs to be better adapted to local needs and contexts, and expanding the most promising programs across entire states and regions. North Carolina’s Healthy Opportunities pilots—which will provide up to $650 million in competitive grant funding over the next five years for housing, food, transportation, and interpersonal safety initiatives aimed at cutting health care costs and improving health outcomes among Medicaid beneficiaries in three areas of the state—exemplify this model clearly (North Carolina Department of Health and Human Services 2020). Consequently, state Medicaid programs have considerable potential to generate positive “spillover effects,” leading by example to springboard the strategies of other health system stakeholders within a community—including the provision of supplemental benefits for the chronically ill and long-term supports and services among Medicare and Medicare Advantage populations, the design of other publicly funded community health interventions, and the improvement of benefits offered in the private insurance market (Daniel-Robinson and Moore 2019).

Challenges – Fragmentation across Medicaid programs generates various roadblocks inhibiting the development of a national strategy to address SDoH

While Medicaid’s built-in flexibility enables individual states’ Medicaid programs to innovate solutions to the health-related social needs facing their communities, it also presents a significant set of drawbacks. For instance, the development of a comprehensive national framework for addressing SDoH needs through government programs like Medicaid is complicated by states’ piecemeal approaches to integrating social interventions into their health care delivery models. A lack of standardization owing to loose federal guidance and oversight generates numerous “trickle-down” challenges, including disjointed data collection, analysis, and reporting; inadequate information sharing both within state health system stakeholder networks and among states; and structural impediments to robust state and regional comparisons that policymakers and key health care actors could leverage to iterate, enhance, and scale existing interventions (Waddill 2019).

Gaps in federal statutory and regulatory infrastructure also exacerbate the free-rider problem Nichols and Taylor discuss as part of their analysis of SDoH interventions as public goods. Risk aversion leads to innovation roadblocks; without proper governance to safeguard investor confidence, state public health authorities and health care payers remain reluctant to commit the time, effort, and resources necessary to kick-start and sustain adequate and effective SDoH interventions because they are wary of legal and financial risks that they perceive to be associated with such programs (Nichols and Taylor 2018). Additionally, mitigating the free-rider problem involves collective action; every health stakeholder in a community must buy into a SDoH intervention in order to reap universally shared benefits. Variation in state Medicaid programs’ capacity encumbers states whose Medicaid programs are not conducive to building and leveraging multisectoral partnerships with community benefit enterprises and other financial, social services, and health stakeholders that operate in those states. Inconsistent practices among states undermine health systems’ ability to coordinate service delivery and evaluation with partners and stakeholders, ascertain individual stakeholders’ willingness to pay for SDoH interventions, and project returns on investment; ultimately, programmatic deficiencies can breed mistrust and impede collaborative innovation required for interventions to advance (Nichols and Taylor 2018). Quality data and accountability undergird success, but the cost of generating and managing timely and accurate data can be prohibitive (Nichols and Taylor 2018). Finally, there needs to be appropriate balance between prescriptiveness and flexibility in Medicaid that incentivizes investment without undermining innovation (Nichols and Taylor 2018).

Recommendations – Focus on building data capacity, promoting creative funding mechanisms, and strengthening partnerships for success

Overcoming and even transforming the challenges of performing crucial SDoH work through state Medicaid programs into opportunities for sustained success requires multi-pronged action on all levels—federal, state, and local—and among all community health system stakeholders. Three primary areas of recommended improvement emerge from the evidence: strengthening state and national capacity for comprehensive, timely, and accurate data collection, analysis, and exchange; promoting the creative use of available financing mechanisms that bridge funding gaps; and innovating existing governance structures in Medicaid to incentivize proactivity and partnership in successfully addressing specific and general SDoH needs at the community level.

Solving data and accountability issues through capacity building. Issues with Medicaid’s data infrastructure directly affecting state programs’ SDoH intervention efforts exist along three axes: insufficiently standardized monitoring, data collection, analysis, and evaluation protocols; inconsistent measurement and operationalization; and unclear expectations surrounding source attribution, transparency, and responsibility.While the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) and the Medicaid and Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP) Payment and Access Commission Advisory (MACPAC) have taken promising steps in recent months to improve Medicaid’s data capacity, considerably more work needs to be done to collect appropriate data, identify at-risk groups, and evaluate the particular health outcomes tied to SDoH interventions (Heberlein 2019). Panel discussions at MACPAC’s December 2019 public meeting revealed that gaps in Medicaid’s current data collection and coordination practices complicate state and federal initiatives to finance innovations in maternal care. Commissioners at the meeting discussed Medicaid’s need to upgrade dated and incomplete data sources and collect better data about race, comorbidities, primary care access and utilization, health care coverage continuity, birthweight, and post-partum health status to properly assess the differential impacts of maternal care initiatives on outcomes like maternal mortality and to justify the merits of funding specific initiatives (Heberlein 2019). Adia et al. (2020) demonstrate the importance of collecting and using granular data for health planning and evaluation purposes through their research about disaggregating health behavior data among Asian subgroups in California that identified health risks specific to subgroups that might have been overlooked when analyzing only aggregate data.Medicaid can adopt the following short-term measures now to resolve its most significant data capacity issues:

- Convene a coalition of federal and state health system representatives that meets regularly to discuss the current state of SDoH innovation, prioritize the biggest data challenges to solve across SDoH domains and communities of interest, promote real-time data and best practice sharing at all levels, and develop and evaluate a data collection and reporting framework to coordinate Medicaid-based SDoH intervention programs; and

- Implement a novel waiver category specific to addressing demonstrated community-level SDoH needs that includes data collection and reporting requirements that allow state programs to conduct robust effectiveness studies and return on investment analyses.

Innovating creative financing solutions to funding shortfalls. To solve the free-rider problem of underinvestment, underprovision, and overutilization of SDoH interventions, all stakeholders forming a community’s health system must equally contribute to interventions and evenly share the collective benefits that result (Nichols and Taylor 2018). Medicaid can take the following actions to incentivize SDoH investment and reduce real and perceived risks involved in jump-starting SDoH innovation:

- Require evidence-based SDoH innovation approaches to be included in requests for proposals and raise allowable “profit rates” to cover the cost of identified interventions;

- Emphasize that beneficiary auto-enrollment rules and algorithms favor health plans that actively generate community-level social benefits (e.g., community benefit affiliated plans and community affiliated networks) and identify and promote financial incentives to priority health plans and communities through MACPAC and state Medicaid agencies;

- Identify strategies to braid and blend funding from different sources—including Medicaid and external financing streams such as grant programs—to achieve SDoH objectives;

- Determine risks and risk sharing structures specific to Medicaid-based SDoH interventions and the legal and financing authorities under which they fall, identify which risks are appropriate for individual health system stakeholders to bear, require all eligible stakeholders to participate in the Medicaid bidding process, hold Medicaid managed care organizations harmless if overall health care expenditures do not increase, and align Medicaid coverage periods for specific populations based on the risks associated with those populations, local contributions made to collective SDoH interventions, and the benefits that accrue from interventions with both short- and long-term payoff windows.

Bolstering federal governance structures to promote impactful partnerships. Collaboration is essential for any SDoH intervention to succeed. Medicaid governance mechanisms can guide organizations and community stakeholders operating within a health system toward more effective communication, more efficient resource sharing, and smarter collective action. Some leading-edge practices for building and sustaining partnerships for SDoH innovation include:

- Defining issue-specific flexibilities, including the set of priority “in lieu of” and upstream “value-added” non-medical social services that influence health outcomes, while recognizing that different solutions exist for different SDoH intervention areas;

- Assessing whether the set of permissible services should differ across populations; and

- Leveraging federal and state regulatory vehicles, SDoH intervention precedent, and existing return on investment evidence to establish clear guidelines for adopting holistic approaches to SDoH that innovate beyond Medicaid and inform a strategic action plans for financing, sustaining, and scaling up the entire spectrum of SDoH intervention areas (Coe et al. 2019).

Conclusion – Medicaid is in a unique position to catalyze lasting impact now

As of April 9, 2020, the coronavirus pandemic is responsible for an average of nearly 2,000 deaths per day in the U.S., firmly establishing COVID-19 as America’s leading cause of daily deaths (Impelli 2020). The damaging impacts of social need and health disparities are particularly evident during the current outbreak: older Americans face even greater difficulties getting access to food; lower-income earners in the service, hospitality, tourism, and travel industries who have lost their jobs can no longer secure health insurance through their former employers; and housing-insecure individuals are disproportionately vulnerable to infection because of their inability to comply with physical distancing recommendations (Impelli 2020). In Maryland, while 30% of the population is Black, over half the state’s deaths from COVID-19 have occurred among Black decedents and an even larger majority of the state’s active unemployment claims were filed by Black workers (Cohn et al. 2020). Medicaid covers or is able to cover many members belonging to each of these population groups. Its federal body and individual state programs uniquely equip it with the scope, reach, authority, expertise, and resource access necessary to overcome structural barriers; catalyze meaningful SDoH investment, innovation, and impact for communities in need across the country; and serve as a 21st century model for effective and inclusive integrated care delivery. The hurdles of COVID-19 provide a window of opportunity for Medicaid and other public assistance programs to reimagine their roles and footprints in America’s communities, enabling them to determine “low-hanging fruit” policies for financing strategies in the short term, strategize realistic timeframes for action in the medium term, and move toward engaging partners for successful and sustained action—starting at the community level and working outward—in the long term.

Figures and Tables

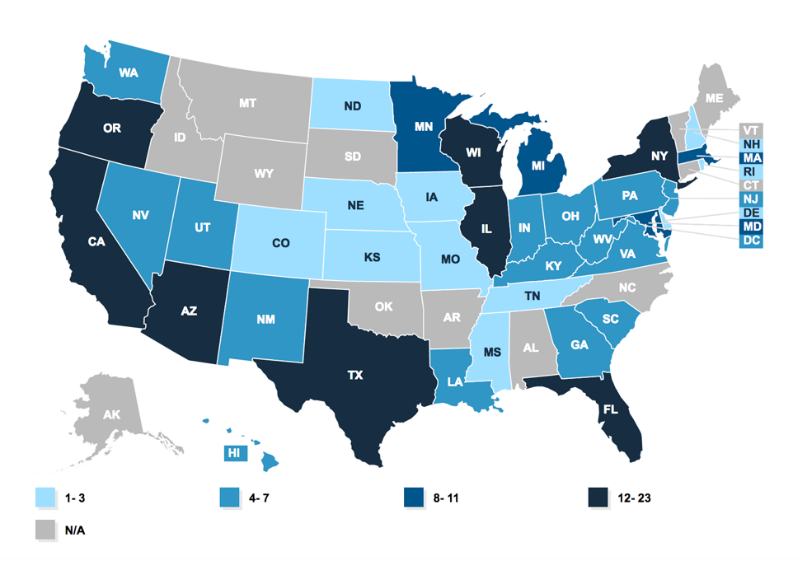

Figure 1. Medicaid Managed Care Organizations (MCOs) by State

Darker blues indicate higher concentrations of MCOs within states.

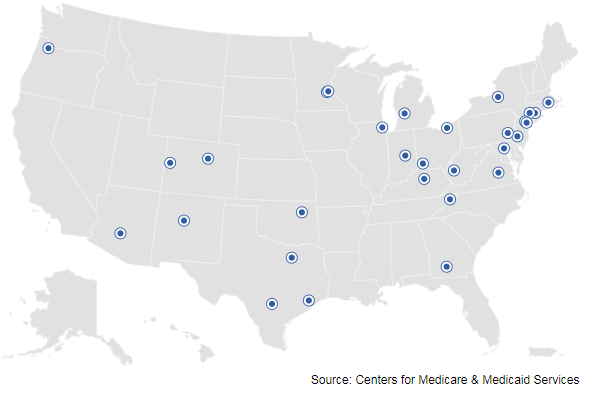

Figure 2. Accountable Health Communities in the U.S.

Accountable Health Communities employ an evidence-based, proactive approach to integrating clinical and community social services to address Medicare and Medicaid beneficiaries’ unmet health-related social needs through screenings, referrals, community navigation services, and evaluation of healthcare costs and utilization.

Table 1. Medicaid-Based Social Determinants of Health (SDoH) Interventions by Focus Area and State

| Social Determinant of Health: | State/s: |

| Education | 7—Arizona, Iowa, Kansas, Massachusetts, Minnesota, New York, Washington |

| Employment and Income | 7—Kansas, Michigan, Minnesota, Tennessee, Washington, West Virginia, Wisconsin |

| Family and Social Supports | 12—California, Kansas, Michigan, Minnesota, New Hampshire, New Mexico, New York, North Carolina, Oregon, Rhode Island, Tennessee, Texas |

| Food Insecurity | 11—California, Florida, Kansas, Michigan, Nebraska, New York, North Carolina, Oregon, Rhode Island, Tennessee, Texas |

| Health Behaviors | 27 + DC—Arizona, California, Colorado, Delaware, District of Columbia, Florida, Indiana, Iowa, Kentucky, Massachusetts, Michigan, Minnesota, Missouri, New Hampshire, New Mexico, New York, North Carolina, Ohio, Oregon, Pennsylvania, Rhode Island, South Carolina, Tennessee, Texas, Virginia, Washington, West Virginia, Wisconsin |

| Health Literacy | 10—California, Kansas, Michigan, New Hampshire, New Mexico, New York, Oregon, Rhode Island, Texas, Washington |

| Housing Instability | 18—Arizona, California, Delaware, Hawaii, Kansas, Louisiana, Maryland, Massachusetts, Minnesota, New Mexico, New York, North Carolina, Pennsylvania, Rhode Island, Tennessee, Texas, Virginia, Washington |

| Interpersonal Violence | 7—Arizona, Kansas, Massachusetts, North Carolina, Rhode Island, Virginia, Wisconsin |

| Legal Needs | 4—Arizona, New Hampshire, North Carolina, Washington |

| Transportation | 3—Kansas, Michigan, North Carolina |

| Utility Needs | 1—Louisiana |

Table 2. Return on Investment Evidence for Community-Level Social Determinants of Health (SDoH) Interventions

| Social Determinant of Health: | Return on Investment (ROI): | Source: |

| Housing Instability | 1 : 1.57 For every additional $1 invested in assisted living, individual home support, and affordable housing, the expected ROI after six months was $1.57 in savings on long-term care and skilled nursing facility costs. | KPMG Government Institute, 2018 |

| Food Insecurity | 1 : 3.87 For every $1 invested in meal delivery services to beneficiaries recently discharged from the hospital, the expected ROI after 24 months was $3.87 in savings due to prevented hospital readmissions. | Martin et al., 2018 |

| Transportation | 1 : 7.68 For every $1 invested in transporting rural Medicare and Medicaid beneficiaries without adequate transportation access to points of care, the expected ROI after 17 months was $7.68 in additional hospital reimbursement. | Alewine, 2017 |

| Home Modification | 1 : 7.08 For every $1 invested in professionally recommended home improvements for meeting beneficiaries’ functional goals, the expected ROI after five months was $7.08 in savings on long-term, outpatient, and inpatient care. | Szanton et al., 2017 |

Bibliography

“Accountable Health Communities Model.” Innovation.CMS.gov. U.S. Center for Medicare and Medicaid Innovation. Accessed April 11, 2020. https://innovation.cms.gov/innovation-models/ahcm.

Adia, Alexander C., Jennifer Nazareno, Don Operario, and Ninez A. Ponze. “Health Conditions, Outcomes, and Service Access Among Filipino, Vietnamese, Chinese, Japanese, and Korean Adults in California, 2011–2017.” American Journal of Public Health, no. 110 (March 11, 2020): 520–26. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2019.305523.

Bachrach, Deborah, Jocelyn Guyer, and Ariel Levin. “Medicaid Coverage of Social Interventions: A Road Map for States.” Milbank.org. Milbank Memorial Fund, July 2016. https://www.milbank.org/publications/medicaid-coverage-social-interventions-road-map-states/.

Boutar, Loujeine, Alyssa Kennedy, and Anina Oliver. “Understanding the Social Determinants of Health: Applying the Grossman Health Capital Model.” PublicPolicy.Wharton.UPenn.edu. Wharton School of the University of Pennsylvania Public Policy Initiative, November 11, 2015. https://publicpolicy.wharton.upenn.edu/live/news/1046-understanding-the-social-determinants-of-health.

Coe, Erica, Marc Berg, Seema Parmar, and Danielle Feffer. “Addressing the Social Determinants of Health: Capturing Improved Health Outcomes and ROI for State Medicaid Programs.” McKinsey.com. McKinsey & Company, April 2019.

Cohn, Meredith, Nathan Ruiz, and Pamela Wood. “Black Marylanders Make up Largest Group of Coronavirus Cases as State Releases Racial Breakdown for First Time.” BaltimoreSun.com. April 9, 2020. https://www.baltimoresun.com/coronavirus/bs-md-coronavirus-race-data-20200409-ffim7y4bljcz3hjk4dmt773mp4-story.html.

Daniel-Robinson, Lekisha, and Jennifer E. Moore. “Innovation and Opportunities to Address Social Determinants of Health in Medicaid Managed Care.” Institute for Medicaid Innovation, January 2019. https://www.medicaidinnovation.org/_images/content/2019-IMI-Social_Determinants_of_Health_in_Medicaid-Report.pdf.

DeSalvo, Karen, and Michael O. Leavitt. “For an Option to Address Social Determinants of Health, Look to Medicaid.” Health Affairs, July 8, 2019. https://www.healthaffairs.org/do/10.1377/hblog20190701.764626/full/.

“Healthy Opportunities Pilots.” North Carolina Department of Health and Human Services. NCDHHS.gov. Accessed April 11, 2020. https://www.ncdhhs.gov/about/department-initiatives/healthy-opportunities/healthy-opportunities-pilots.

Heberlein, Martha. “MACPAC December 2019 Public Meeting.” MACPAC December 2019 Public Meeting. December 13, 2019.

Hood, C.M., K.P. Gennuso, G.R. Swain, and B.B. Catlin. “County Health Rankings: Relationships Between Determinant Factors and Health Outcomes.” American Journal of Preventive Medicine 50, no. 2 (October 31, 2015): 129-35. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2015.08.024.

Impelli, Matthew. “Coronavirus Becomes Number One Cause Of Death Per Day In U.S., Surpassing Heart Disease and Cancer.” Newsweek.com. April 9, 2020. https://www.newsweek.com/coronavirus-becomes-number-one-cause-death-per-day-us-surpassing-heart-disease-cancer-1495607.

Manatt Health, and Phelps and Phillips, L.L.P. “Medicaid’s Role in Addressing Social Determinants of Health.” RWJF.org. Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, February 2020. https://www.rwjf.org/en/library/research/2019/02/medicaid-s-role-in-addressing-social-determinants-of-health.html.

“Medicaid Managed Care Market Tracker.” KFF.org. The Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation, March 5, 2020. https://www.kff.org/data-collection/medicaid-managed-care-market-tracker/.

Nichols, Len M., and Lauren A. Taylor. “Social Determinants as Public Goods: A New Approach to Financing Key Investments in Healthy Communities.” Health Affairs 37, no. 8 (August 2018): 1223-1230. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2018.0039.

Schwartz, Rachel. “Medicaid Policy in 2019: Social Determinants of Health.” EssentialHospitals.org. America’s Essential Hospitals, June 25, 2019. https://essentialhospitals.org/medicaid-policy-2019-social-determinants-health/.

Tsega, Mekdes, Corinne Lewis, Douglas McCarthy, Tanya Shah, and Kayla Coutts. “Review of Evidence on the Health Care Impacts of Interventions to Address the Social Determinants of Health.” CommonwealthFund.org. The Commonwealth Fund, July 1, 2019. https://www.commonwealthfund.org/publications/2019/jun/roi-calculator-evidence-guide.

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. “Social Determinants of Health,” HealthyPeople.gov. HHS Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion. Accessed April 11, 2020. https://www.healthypeople.gov/2020/topics-objectives/topic/social-determinants-of-health

Waddill, Kelsey. “Challenges of Investing in Social Determinants of Health.” HealthPayerIntelligence.com. Health Payer Intelligence, August 6, 2019. https://healthpayerintelligence.com/news/challenges-of-investing-in-social-determinants-of-health.

World Health Organization Commission on Social Determinants of Health. “Closing the Gap in a Generation: Health Equity through Action on the Social Determinants of Health.” WHO.int. World Health Organization, November 15, 2019. https://www.who.int/social_determinants/en/.