by Benjamin Keeler

Since its inception, Nigeria has seen insurgencies by non-state political actors. Beginning with the Maitatsine crisis in 1980-1982 and moving into the 21st century with the Movement for the Emancipation of the Niger Delta (MEND) and the Ombatse cult group. Beginning in 2009, a new insurgent group appeared, Boko Haram, threatening the territorial integrity and governing authority of the Nigerian state. Beginning in 2010, the Nigerian government pursued an aggressive military campaign against the group but after peaks in violence between 2014-2015, it became clear that Nigerian unilateral efforts to defeat Boko Haram had failed. In this timeframe, new effort was put into the development of a regional security infrastructure, namely the Multinational Joint Task Force (MNJTF), an already existing regional security organization and the External Intelligence Response Unit (EIRU), a collaborative intelligence sharing unit with the United States, United Kingdom, France, Benin, Chad, Cameroon, and Niger.

Soon after this effort, a coordinated military campaign between Nigeria, Benin, Cameroon, Chad, and Niger pushed Boko Haram out of several northeastern Nigerian provinces. However, the group still holds small pockets of territory and is able to coordinate suicide attacks and abductions of civilians. To what extent has development of a regional security infrastructure in response to Boko Haram been successful? The conflict in Nigeria and the Lake Chad Basin, but more importantly the government response, serves as a critical case study in multilateral and regional security cooperation. Lessons learned from the MNJTF and ERIU will be essential in developing future regional security and counterterror infrastructures. While the MNJTF was an effective first step in eradicating the threat of terrorism, it does not go far enough to fully eliminate the threat; the MNJTF successfully externalized the conflict and did significantly reduce levels of violence from 2015 to present day, but structural flaws, including mistrust, intelligence sharing, human rights abuses, and the lack of a whole of government approach hamper the full stabilization of Nigerian territory and the broader Lake Chad Basin region.

When studying Boko Haram, it is important to understand the origins of the group. Boko Haram is a Hausa name, and its Arabic translation is, “Jama’atu Ahlis Sunna Lidda’awati Wal-Jihad (“People Committed to the Propagation of the Prophet’s Teachings and Jihad.”) Boko Haram began as a local radical salafist movement in the mid 1990s but developed into a Salafist jihadi terrorist organization in 2009. While Boko Haram has its origins in Nigeria, the war has extended beyond its borders. By externalizing the conflict, Boko Haram has managed to gain support from other terrorist groups, including fighters, weapons, technical and tactical knowledge. In his paper, The Nature of Nigeria’s Boko Haram War: A Strategic Analysis, Dr. Adewunmi Falode offers a useful timeline of the conflict with Boko Haram. He divides the conflict into three iterations. The first is from 1997-2002, when its activities were viewed as civil unrest by the Nigerian government. From 2002-2009, it became known as a religious uprising. Between 2010 and 2015, the war took its most recent form, a war on terror from the perspective of the Nigerian government, and an insurgency by Boko Haram. Dr. Falode goes on to discuss the development of the MNJTF, contending that Nigeria used the MNJTF to broaden the scope of the operations against Boko Haram. The development of the MNJTF and creation of the EIRU helped achieve two key strategic objectives. The first was that it compelled neighboring states like Cameroon to assist in securing its porous borders, stemming the flow of fighters moving across international boundaries. Secondly, and more importantly according to Falode was that the new regional and multilateral nature of the conflict allowed Nigeria to gain key international military and political support. In 2015, following the MNJTF and the EIRU, the Nigerian government signed an agreement with the United Kingdom where the British military would train Nigerian forces on COIN tactics for the next 20 years. Dr. Falode provides an excellent characterization of the nature of the war with Boko Haram and the key role the expansion of the MNJTF and the EIRU had in the externalization of the conflict.

The MNJTF is also viewed within the broader context of a transnational security threat and a regional security infrastructure. Usman A. Tar and Mala Mustapha explain this context in their paper, The Emerging Architecture of a Regional Security Complex in the Lake Chad Basin. Tar and Mustapha contend that the use of this new security mechanism in the Lake Chad Basin is driven by three factors, resource geopolitics, regional security, and Nigeria’s desire for hegemonic stability. They go on to argue that the current form of the MNJTF was a drastic change from its original form, altering the regional security posturing specifically towards the regional threat of Boko Haram due to the failure of the Nigerian government to unilaterally defeat the terrorist group. The election of Muhamnmadu Buhari as the President of Nigeria in 2015 emboldened the MNJTF with a new sense of urgency and political will. A key point of Buhari’s campaign platform was ending Boko Haram. Immediately following his election, Buhari reformed command structures and increased cooperation with Cameroon, Chad, and Niger. Most notably, a bilateral treaty between Nigeria and Chad allowed Chadian troops to cross the border into Nigerian territory if they were in the pursuit of Boko Haram. Despite gains and progress in multilateral cooperation, Boko Haram attacks continue across the Lake Chad Basin. Tar and Mustapha assert that continued multilateral cooperation is necessary for the defeat of Boko Haram, but acknowledge the limitations of the MNJTF.

Regardless of the robust nature of the MNJTF, there are still challenges inherent with their operations. These flaws are explored in by Stanley Ehiane and Bheki Mngomezulu. Ehiane and Mngomezulu scrutinize Nigeria’s approach to counterterrorism and establishes why their government has failed. They argue that despite the bilateral and multilateral cooperation facilitated through the MNJTF, a series of limitations have impeded successful operations, including human rights violations and ineffective intelligence gathering mechanisms. Indiscriminate airstrikes by the Chadian military and extrajudicial killings of suspected terrorists by various security agencies have raised red flags by many human rights organizations, to include Amnesty International. They contend that ineffective intelligence sharing within the MNJTF has hampered effective targeting in joint operations. Ehaine and Mngomezulu’s article plays an important role, drawing attention to the limitations and flaws of the MNJTF, which must be addressed to develop a more comprehensive and effective security infrastructure in the Lake Chad Basin.

To understand regional security in the Lake Chad Basin, one must look to Charles Kupchan, who takes a theoretical approach to transnational security. He defines a security community as “a zone within which states have stable expectations of peaceful change – and those that continue to play by more traditional rulers of geopolitics” Kupchan provides an important lens by which to examine the MNJTF, and the broader security community being developed in the Lake Chad Basin. The most notable element of the theory of security communities is that nations with similar threats would work together to provide a safe environment for themselves, especially considering that the international system is anarchical in nature. (Kupchan 2001) The security infrastructure developed by MNJTF member nations for the Lake Chad Basin reflects this theory. The MNJTF emulates realism, in that it recognizes the need for shared security burdens in an anarchical system, that the ongoing Boko Haram crisis in Nigeria was not solely a Nigerian problem, but a regional one. Despite its structural limitations and unique challenges, the development of the MNJTF was a successful first step in the multilateral cooperation necessary to eradicate the threat of terrorism in the Lake Chad Basin. The MNJTF successfully externalized the conflict and significantly reduced levels of violence from 2015 to present day. However, ineffective intelligence sharing, a myriad of human rights abuses, and a lack of whole of government approach hamper the full stabilization of the Lake Chad Basin, and Nigeria in particular.

One of the two main successes of the MNJTF is that it successfully externalized the conflict. Transnational approaches are necessary to defeat transnational threats. Through multilateral operations and by characterizing Boko Haram as a regional threat, the MNJTF was able to secure financial, military, and political support of actors invested in regional stability and the eradication of terrorist groups. This funding, military and technical support created a significantly more effective fighting force. One example of political and military support comes from the European Union, United Kingdom, and the United States. France and the US provide military aid directly to MNJTF troop contributing countries (TCC). Additionally, the United Kingdom provides financial support to the MNJTF through the African Union. The EU designates funding for the MNJTF as well, covering costs associated with personnel, logistics, and operations. Financial and operational support from partner nations like the European Union and the United States have bolstered the militaries of MNJTF nations.

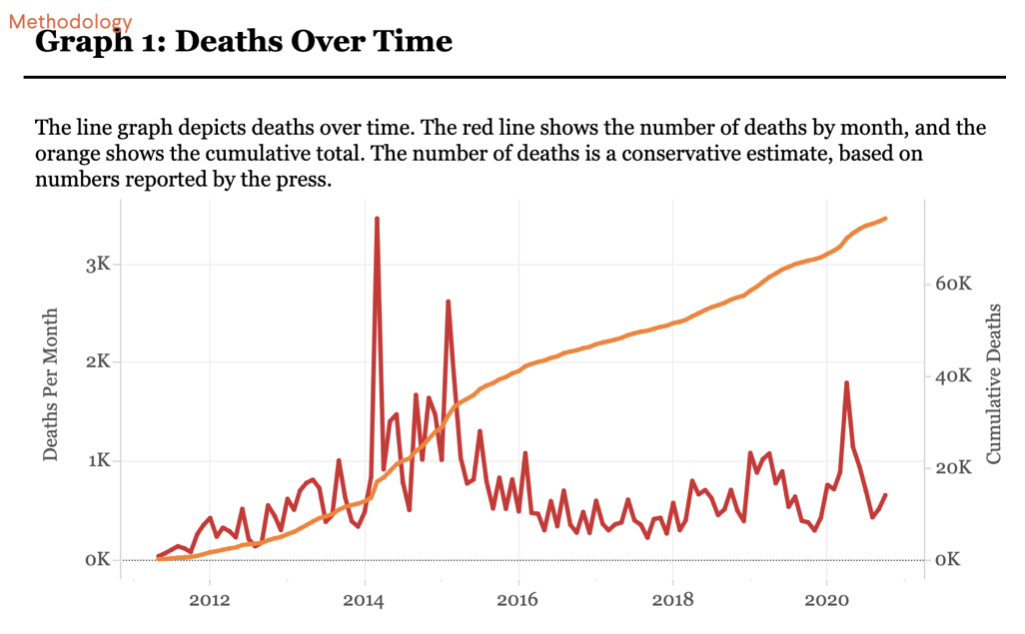

The other success of the MNJTF is empirical in nature. Since 2014, the number of deaths driven by the Boko Haram have drastically decreased in Nigeria, the main theatre of the conflict. The Council on Foreign Relations Nigeria Security tracker catalogs political violence based on weekly surveys of Nigerian and international press. This data is then sorted into more narrow categories. Below, is a graph of deaths over time.

As violence rose in 2014-2015, the international community had little confidence in Nigeria’s ability to defeat Boko Haram. Two attacks in particular caught international media attention. The bombing of an Abuja Bus station in in 2014 claimed the lives of nearly 100 people. The kidnapping of more than 200 schoolgirls in the town of Chibok prompted an massive international outcry and criticism of the Nigerian government for a lack of an effective response. After the reorienting of the MNJTF to a counterterrorism mission in 2015, deaths decreased. This is not simply a correlation. Increased counterinsurgency operations by the multinational force created conditions where Boko Haram was forced to shrink their physical footprint and go into hiding. (Falode 2016)

By framing Boko Haram as a regional threat, and treating it as such, the MNJTF was able to significantly reduce deaths caused by Boko Haram since 2014-2015. While reliable data about the broader Lake Chad Basin is difficult to obtain, it can be inferred that a reduction in deaths in the main theater of the conflict would reflect broader trends in the region. If the deaths decrease in the main theatre of the conflict, they will across the board. By framing Boko Haram as a threat to the region the MNJTF reduced deaths from Boko Haram significantly from the peaks in 2014-2015.

While the MNJTF did successfully reduce deaths associated with the conflict and externalize the conflict, there are still significant structural factors which limit the effectiveness of the MNJTF. The first factor is trust. Within the member nations, there are significant issues which lead to a lack of trust. The relationship between Nigeria and Cameroon is apprehensive at best, stemming from the Bakassi Crisis. The Bakassi peninsula was a part of Nigeria but was claimed by Cameroon as well. This led to several military encounters between the two nations, where civilians died on both sides. To this day, the two countries are unable to come up with a way to mediate the conflict. The lack of trust on both sides is a significant barrier to cooperation. Nigeria also has a border dispute with Chad. The conflict between Nigeria and Chad is far more severe than that of Nigeria and Cameroon. Chad contests Nigerian claims to parts of Lake Chad. Due to lack of clear demarcation, border villages are left to themselves to determine what belongs to Chad and what belongs to Nigeria. Many of the disputed villages have valuable fishing and mineral resources. These tensions led to a military conflict in 1983, with deaths being recorded on both sides. Historical mistrust between the member states of the MNJTF presents a significant barrier to future cooperation, even with the shared threat of Boko Haram. Chad’s issues with internal stability also pose severe limitations to the MNJTF. From 1978-1983, Chad fought a civil war which negatively impacted Nigeria’s trade with the country and led to a stream of Chadian refugees and armed rebel fighters flowing into Nigeria. In 2002, the Governor of Borno State complained that his state was plagued by an influx of armed rebels, and large-scale arms and human trafficking. Many of these rebels used the Sambisa Game Reserve as a hideout, and it still is a security threat to Nigeria today. The governor claimed that the rebels were responsible for widespread violence, trafficking and banditry in the area. The Chadian civil war also allowed for the massive entry of arms, stemming from military assistance by France and the United States. Nigeria is not comfortable with any of its neighbors being so well armed, this has led to Nigeria being suspicious of Chad. Most concerning for Nigeria, was Libya’s support for the Chadian government under the regime of Gadhafi. Gaddafi was no friend to Nigeria. Over the course of his rule, Libya attempted to instigate several Islamic Revolutions using different groups. These conditions led to Nigeria supporting the United Nations Resolution Council 1973, which authorized the use of force in degrading the Libyan military capabilities to protect civilian lives. In the long run, the destabilization of Libya worsened Nigeria’s security situation, with fighters and arms from that conflict flowing to Nigeria and supplementing Boko Haram.

Less than cordial relationships with both Cameroon and Chad made it difficult for Nigeria to approach those states for assistance and cooperation with fighting Boko Haram. Chad played a bystander role at the onset of the conflict, claiming they were unaware of Boko Haram fighters using their country as a safe haven. After accusations from Nigeria that they were supporting Boko Haram, and terrorist attacks targeting their own citizens both Chad and Cameroon began to take military action against the group. Boko Haram responded by declaring them enemies. This made the Boko Haram crisis a regional issue, allowing for Cameroon and Chad to work collaboratively with Nigeria through the MNJTF. Despite the existence of the MNJTF as a mechanism by which to collaborate, old mistrust and suspicions remain. Nigeria does not trust Cameroon or Chad, and those nations do not trust Nigeria. While a recent treaty allows Chadian troops to cross the Nigerian border when in hot pursuit of insurgents, cross border operations are not liked by the Nigerians. To an extent, they are viewed as invasions, and violations of territorial integrity. Nigeria would prefer that insurgents are chased to the border, and then finished off by Nigerian forces. However, this is not necessarily operationally or logistically feasible, especially with ineffective communication due to the aforementioned historical mistrust. There is a significant communication barrier within the MNJTF as well, driven by mistrust, but also a language barrier. As a general trend, Nigerian soldiers do not understand French and the soldiers of all other troop contributing nations speak French, and do not understand English. A security community that cannot effectively communicate or establish some sense of mutual trust and understanding cannot succeed in its shared objective.

Intelligence gathering has been another shortcoming of the MNJTF. Poor intelligence gathering by member state agencies has resulted in confusion which has hampered operational capability. Strong intelligence strengthens and coordinates the execution of counter-terrorist operations. Intelligence agencies exist within the Nigerian Army and the Nigerian Police Force, and have a mandate to support military operations, but lack proper manpower, technology, and know how to be effective. In a study of Nigerian counterterrorism mechanisms, it was revealed that weak advanced monitoring technology (AMT) impedes counterterrorism operations. The absence of biometric identification systems like fingerprinting at Nigeria’s borders allows for foreign fighters from Libya and Mali to go into Nigeria unimpeded. Apart from biometrics at the border, Nigeria, and the MNJTF as a whole does not have a DNA database. Without a database, or biometric identification systems, member states of the MNJTF are not able to identify who comes in their country, allowing for a flow of foreign fighters to continue. A DNA database would allow for forensic intelligence to be gathered at the scenes of bombings and other mass attacks, providing essential information to determine terrorist group members and structures. In the status quo, this policy solution is not feasible. More training and funding from partner nations could build this capacity. Nigeria lacks both the qualified manpower, funding and technology to conduct these types of intelligence operations. The External Intelligence Response Unit (EIRU) mitigates some of the intelligence shortcomings, but does not do enough to adequately train, staff, and develop intelligence capability in the Lake Chad Basin. Nigeria and other MNJTF member states must have organic intelligence capability. Reliance on the US, UK and France for intelligence is not sustainable in the long term.

Another limitation on the MNJTF has been a history of human rights abuses by member states. These abuses damage the credibility of the MNJTF and prevent full international political and military support of their operations. Chadian airstrikes targeting terrorists have led to unintended casualties. There are also numerous reports of the extrajudicial killings and torture of suspected terrorists. In 2019, Human Rights Watch reported that the Nigerian military detained thousands of children in inhumane conditions because of their suspected involvement and association with Boko Haram. Nigerian authorities detained children with little to no evidence of crime. The victims of this abuse described a pattern of little food, frequent beatings, and detainment in tightly packed cells.

Based on findings above, shortcomings within the MNJTF which must be addressed in order to stabilize the Lake Chad Basin. The organization’s counterterrorism cooperation is quite robust and a significant first step to the eradication of Boko Haram. The overall success of the MNJTF in reducing violence and externalizing the conflict indicates the importance of continued regional cooperation. As Boko Haram’s physical and propagandic footprint has transcends borders, counterterrorism strategies must do the same. The MNJTF should strengthen its multilateral commitment to the eradication of Boko Haram, and work towards building more trust within its member states to facilitate more effective communication and operational synergy. The Nigerian government should continue to seek training and funding from the European Union, United Kingdom, and United States particularly to develop their intelligence capability, a necessary component in counterterror operations. Steps must be taken to address human rights abuses by government authorities to build credibility within the international community and their own populations.

There are similarities between the activities of Boko Haram in the Lake Chad Basin and Al-Shabab in Kenya and Somalia. However, Boko Haram has consistently changed strategy and targets since its founding. Al-Shabab has maintained strategic consistency. While the two conflicts have some differences, the regional nature and cross border tendencies of the two groups indicate that studying them in a comparative context is important for developing regional counterterrorism strategies. The development of a robust, African led, multilateral organization dedicated to combating the threat of Al-Shabaab is a possible solution to instability in the Horn of Africa. The comprehensive nature of the MNJTF could serve as a framework, but more importantly its shortcomings can offer important lessons in developing new regional security infrastructures.

Works Cited

Amnesty International (2014). ‘Nigeria: More than 1,500 Killed in armed conflict in North-Eastern Nigeria in early 2014.’ Amnesty International Publications, London

Campbell, John. “Nigeria Security Tracker.” Council on Foreign Relations. Council on Foreign Relations. Accessed November 20, 2020. https://www.cfr.org/nigeria/nigeria-security-tracker/p29483.

Dalton, Melissa G., Hijab Shah, Shannon N. Green, and Rebecca Hughes. Oversight and Accountability in U.S. Security Sector Assistance: Seeking Return on Investment. Report. Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS), 2018. 29-33. Accessed December 11, 2020. doi:10.2307/resrep22422.7.

Ehiane, Stanley O., and Bheki R. Mngomezulu. “Issues in Nigeria’s Counter-Terrorism Mechanisms: Prospects for Regional Cooperation to Fight the Scourge.” Journal of African Union Studies, vol. 7, no. 2, 2018, pp. 63–83. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/26889809. Accessed 6 Oct. 2020.

IRIN, 2002, ‘Nigeria: Border Issues around Lake Chad Cause Concern’, IRIN, www.irinnews.org/report/34503/nigeria-border-issues-around-lake-chadcause-concern

James A. Falode. 2016. The Nature of Nigeria’s Boko Haram War: 2010-2015 A Strategic Analysis. Perspectives on Terrorism 10(1): 41-52.

Johnson, I.J., 2014, ‘Inter-security Agencies Conflict at Nigeria’s Borders: A Challenge to Nigeria’s National Security’, International Journal of Humanities and Social Science 4 (7) May: 211–16

Kupchan, C.A., 2001, ‘Empires and Geopolitical Competition: Gone for Good?’ in Crocker, C.A., Hampson, F.O. and Aall, P., eds, Turbulent Peace: The Challenges of Managing International Conflict, Washington DC: United States Institute Press

Mbah, Fidelis. “Nigeria’s Chibok Schoolgirls: Five Years on, 112 Still Missing.” Nigeria | Al Jazeera. Al Jazeera, April 14, 2019. https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2019/4/14/nigerias-chibok-schoolgirls-five-years-on-112-still-missing.

Mockaitis, T.R (2008). The new terrorism: Myths and reality. California: Stanford University Press

“Nigeria: Military Holding Children as Boko Haram Suspects.” Human Rights Watch, October 28, 2020. https://www.hrw.org/news/2019/09/10/nigeria-military-holding-children-boko-haram-suspects.

Nossiter, Adam. “Nigeria Blast Kills Dozens as Militants Hit Capital.” The New York Times. The New York Times, April 14, 2014. https://www.nytimes.com/2014/04/15/world/africa/nigeria.html.

“Projects.” Multinational Joint Task Force (MNJTF) against Boko Haram | The Africa-EU Partnership. Accessed November 20, 2020. https://africa-eu-partnership.org/en/projects/multinational-joint-task-force-mnjtf-against-boko-haram.

Tar, Usman A., and Mala Mustapha. “The Emerging Architecture of a Regional Security Complex in the Lake Chad Basin.” Africa Development / Afrique Et Développement, vol. 42, no. 3, 2017, pp. 99–118. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/90018136. Accessed 6 Oct. 2020.

Tarlebbea, K.N. and Baroni, S., 2010, ‘The Cameroon and Nigeria Negotiation Process over the Contested Oil rich Bakassi Peninsula’, Journal of Alternative Perspectives in the Social Sciences, Nova Southeastern University (Fort Lauderdale, Florida) 2 (1): 198–210.

Also published on Medium.