by Tangy Sarazin

Abstract

Does an individual’s political party affiliation or income level influence their views regarding the importance of reducing income inequality? Structural position and social identity theory suggest that individuals who are disadvantaged by a system will be more likely to oppose said system than those who benefit from it. However, system-justification theory and other studies suggest that the amount of inequality-legitimizing myths and meritocratic principles a society or group is exposed to may not reproduce this result, in fact, it is suggested that the disadvantaged groups could be just as likely, if not more likely, than their privileged counterparts to support current levels of inequality. In order to test both these theories in American this study uses a mixed methods approach to examine the influence political party affiliation and income has on one’s views towards reducing income inequality. The results of the study suggest that democratic party affiliation is positively correlated with one’s views towards reducing income inequality, while it also suggested that there is a weak statistical significance in a relationship between higher income and unfavorable views of reducing income inequality.

Introduction

In this paper I attempt to examine the influence income level and political party affiliation have on an individual’s view towards the importance in reducing income inequality. The current COVID-19 pandemic has brought America’s growing income inequality problem back to the front of American minds. The economic stressors such as unemployment and insufficient financial assistance to the working class that have been brought on by this pandemic has caused a shift in political discussions about the importance in reducing this growing level of income inequality in America (TIME Magazine 2020). So, after the big business bailout, why do some Americans still not view reducing income inequality as all that important? To answer this question, I wanted to look at how the variables of political party affiliation and income level may be affecting how important one views reducing income inequality. Current literature on the subject varies. The structural position and social identity theories suggest that those disadvantaged by a system will be more opposed to said system than their privileged counterparts (Hadler 2005; Osberg and Smeeding 2006). However, newer research suggests that this is not the only result observed. Some studies and the system-justification theory suggests that in societies or groups with higher exposure to inequality-legitimizing myths and meritocratic principles that the disadvantaged individuals can be just as likely, if not more likely, than their high status, privileged counterparts to support current levels of inequality (Roex et al 2018; Zimmerman and Reyna 2013). The rest of the paper is as follows. In the first section I will present a literature review of related material on this subject. In the second section I will present this paper’s main theory and hypotheses. The third section explains the methods that were used in this study and the fourth section presents the results and discussion of the findings. In the final section I will conclude the paper and present suggestions for further inquiry into the subject.

Literature Review

This study attempts to examine the effect an individual’s political party affiliation and income level has on their view of the importance in reducing income inequality. An increasing amount of literature has demonstrated how attitudes towards income inequality can differ between groups and individuals within societies (Hadler 2005; Osberg and Smeeding 2006), also on how they can differ between societies and groups (Roex et al 2018; Zimmerman and Reyna 2013). Most literature focuses on how it is to be expected that higher status individuals (high income and/or education levels) are more likely to be supportive of current systems and levels of inequality because they are the current beneficiaries of said inequality , therefore they will reject the idea of changing the system based on the structural position and social identity theories (Hadler 2005; Osberg and Smeeding 2013). The structural position theory suggests that individuals with high status in a society will oppose change to structures in that society in order to sustain, or further, their privilege (Hadler 2005), this theory was later confirmed in other studies (Osberg and Smeeding 2013, Larsen 2016). The social identity theory suggests that individuals will do what they can in order to achieve or maintain a positive social identity and that members among both classes will oppose practices that challenge their groups positive social identity (Tajfel and Turner 1979). This suggests that high status individuals will protect structures that give them their privilege and that lower status individuals will reject practices or structures that degrade their social identity and self-esteem.

However, there have been cases studied that did not support the above theories. There are cases where low status groups can be just as likely, or even more likely, than high status groups to accept and support current inequality (Roex et al 2018; Zimmerman and Reyna 2013, Jost 2001). One idea is that in societies with strong meritocratic principles inequality is more legitimized and therefore easier justified by groups at both ends of the income spectrum (Roex et al 2018; Zimmerman and Reyna 2013; Larsen 2016). The theory is that in meritocratic societies hard work is seen as the main indicator of success, therefore the process that creates inequality can be looked at as a fair process and the inequality becomes justified, even in these disadvantaged groups (Roex et al 2018, Brandt 2013). This is described as the system-justification theory, it suggests that in certain circumstances low status individuals will support current levels of inequality just as much as their high-status counterparts due to how legitimized the system can be (Brandt 2013).

Theory and Hypotheses

This study suggests that an individual’s income level or political party affiliation influences their attitude towards the importance of reducing income inequality. I chose the variable of political party affiliation because political party identification and that party’s ideology can help define an individual’s ideals and attitudes towards certain political issues. In the United States there are two major political parties, the Republican Party and the Democratic Party. I expect that people who affiliate with the Republican Party will be less likely to view reducing income inequality as important than their Democratic counterparts. As discussed in earlier literature, individuals who are exposed to stronger meritocratic principles and inequality-legitimizing myths are more likely to support current levels of inequality, therefore, not viewing reducing it as important. The Republican party is a right-wing, conservative political party that is abrasive of redistributive tax policy and social programs to help the disadvantaged. The Republican party is also known to espouse more inequality-legitimizing myths, such as ‘pull yourself up by your bootstraps’. Therefore, I expect members of their party to be more comfortable with current levels of income inequality and not view reducing it as very important at all. The Democratic Party is a more left-leaning, liberal political party that is much more embracing of redistributive tax policy and the strengthening and expanding of social welfare programs along with expanding the middle class. Therefore, I expect individual’s who affiliate with the democratic party to be more likely to view reducing income inequality as an important duty of government. I also theorize that we may find individuals with higher income levels to be less likely to view reducing income inequality as important and necessary. I suspect this because individuals with higher incomes currently benefit from current levels of income inequality and through the structural position and social identity theories these individuals would oppose any changes to the current structure in order to maintain or expand their wealth.

H1: Individuals who affiliate with the Democratic party will view reducing income inequality as more important than individuals who affiliate with the Republican party.

H01: Individuals who affiliate with the Democratic party will not view reducing income inequality as more important than individuals who affiliate with the Republican party.

H2: Individuals with higher scales of income will be less likely to view reducing income inequality as important than individuals with lower scales of income.

H02: Individuals with higher scales of income are not less likely to view reducing income inequality as important than individuals with lower scales of income.

Methods and Data

In this paper I use a mixed methods approach that includes a multivariate linear regression of the independent variables (political party affiliation, scale of income) and the dependent variable (views on importance of reducing income inequality) using the World Values Survey: Wave Six dataset that surveys the United States. I will also be using a single illustrative case study to help support the statistical findings in the data analysis. In this study I am asking whether party affiliation or scale of income will influence how important an individual’s views the reduction of income inequality. For the dependent variable I turn to the WVS dataset V137, views on whether reducing income inequality is an essential characteristic of democracy. This variable is measured ordinally on a scale of one to ten, one meaning not at all an essential characteristic and ten meaning definitely an essential characteristic. I chose this indicator because it represents my variable closely. It asks the participants of the study how essential they view reducing income inequality which is what I want to measure for my dependent variable. For my first independent variable I want to measure political party affiliation. I looked at V288 from the WVS database that asked participants if there was a national election held tomorrow, which party would they vote for. This is a nominally measured ration which I transform into a binary nominal variable in order to only study individuals who responded to the Republican party or the Democratic party. I chose this measure rather than one that measures political ideology on a left/right political scale because I specifically wanted to look at political parties and how they can influence an individual’s views, rather than measure an individual’s overall ideology. I also chose this indicator because I wanted to look at party loyalists who are more likely to simply subscribe to the views of the party, they are loyal to, no questions asked. I believe looking at party loyalists will more accurately measure this effect. The second independent variable, income level, I chose V139 from the WVS as an indicator. This indicator is measured ordinally on a scale from one to ten, one meaning lowest income scale and ten meaning highest income scale. I chose this measure over a measure of social class because this indicator offered more variation in order to obtain a more reliable measure. I pulled the data from the World Values Survey, Wave Six, and I specified it for the United States. The WVS uses stratified random sampling at the country level. I use a multivariate linear regression with the ordinary least squares approach. I believe this statistical test is more robust as compared to the difference of means and correlation coefficient tests, also because the dependent variable is measured ordinally on a scale of one to ten. For each observation the following equation is applied.

Views on the importance of reducing income inequality= α+(β1*party affiliationi)+(β2*scale of incomei)

In addition to quantitative analysis, a qualitative approach is also utilized to help support findings from the above statistical analysis, in this I conduct an illustrative case study and then conduct a content analysis. I survey a convenience sample of four individuals that I believe accurately represent the research population. I conducted semi structured interviews with participants that lasted for around 25 minutes. I started with asking the participants the same question used to measure the dependent variable from the WVS survey, V137. After this I would then ask the participants how long they had held this viewpoint and if they could identify any influences in their life that may have helped them formulate this viewpoint. I then moved onto discussing which political party they affiliated with most and also how long they had affiliated with said party and if they could identify any influences that may have helped form this affiliation. I then performed extensive content analysis on these interviews.

Results and Discussion

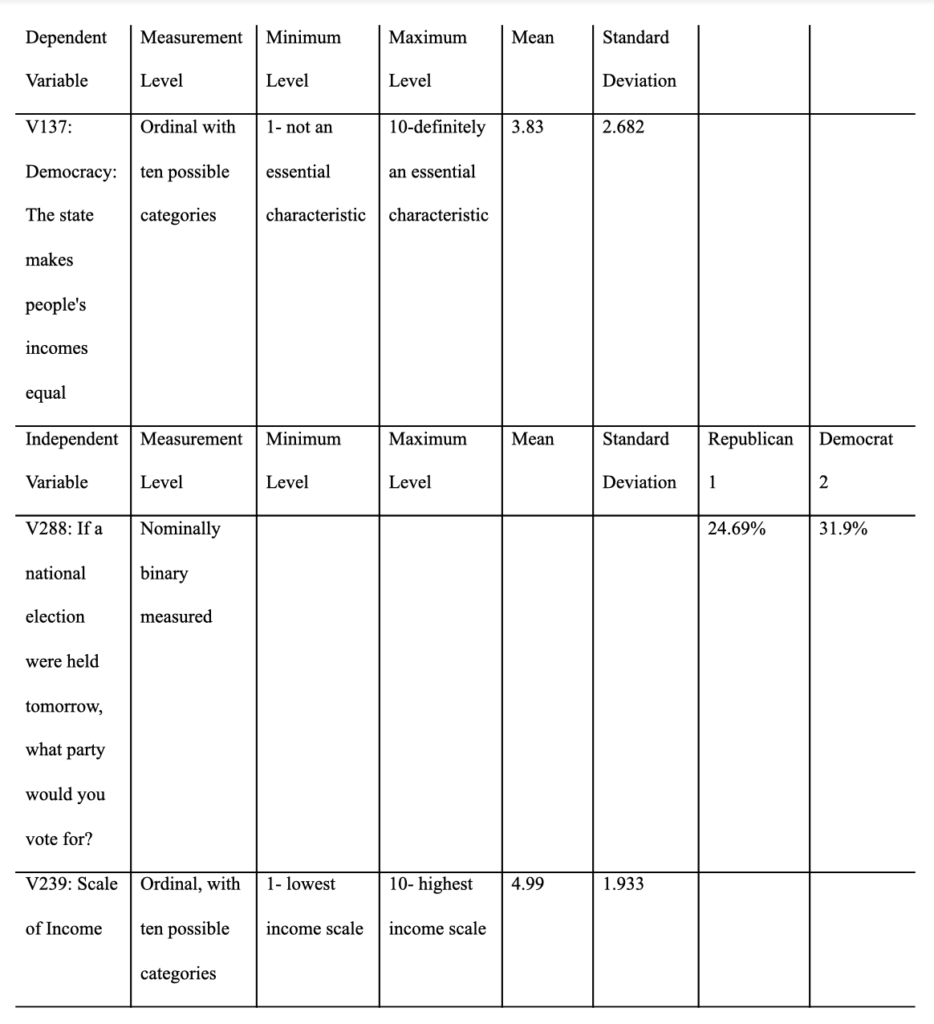

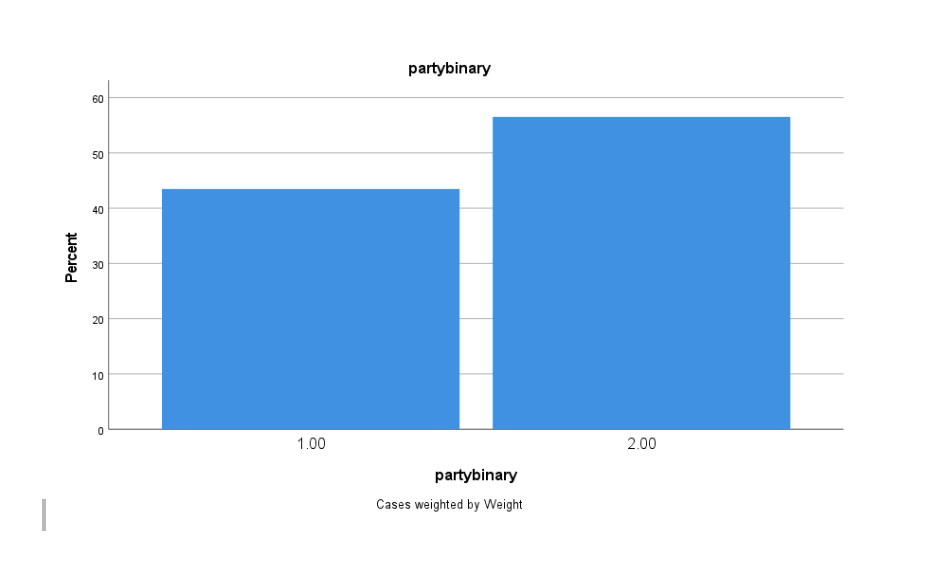

This data summary shows that the dependent variable, V137, has a minimum value of one, meaning that the participant does not view reducing income inequality as important and ten meaning the participant definitely views reducing income inequality as important. This variable has a mean of 3.83 and a standard deviation of 2.682, which suggests that this data is dispersed widely around the mean, the data varies greatly. The first independent variable, V288, measures political party affiliation and has been transformed into a binary variable in order to only look at Republican (1) or Democrat (2) observations, therefore 43.5% of the data is missing. The data that is missing is individuals who selected the responses “I don’t know” and “Would not vote”. The second independent variable, V239, asks participants what their scale of income is and has a minimum value of 1 (lowest income step) and maximum value of 10 (highest income step). This variable has a mean of 4.99 and a standard deviation of 1.933 which suggests most of the participants are in the middle scale of income.

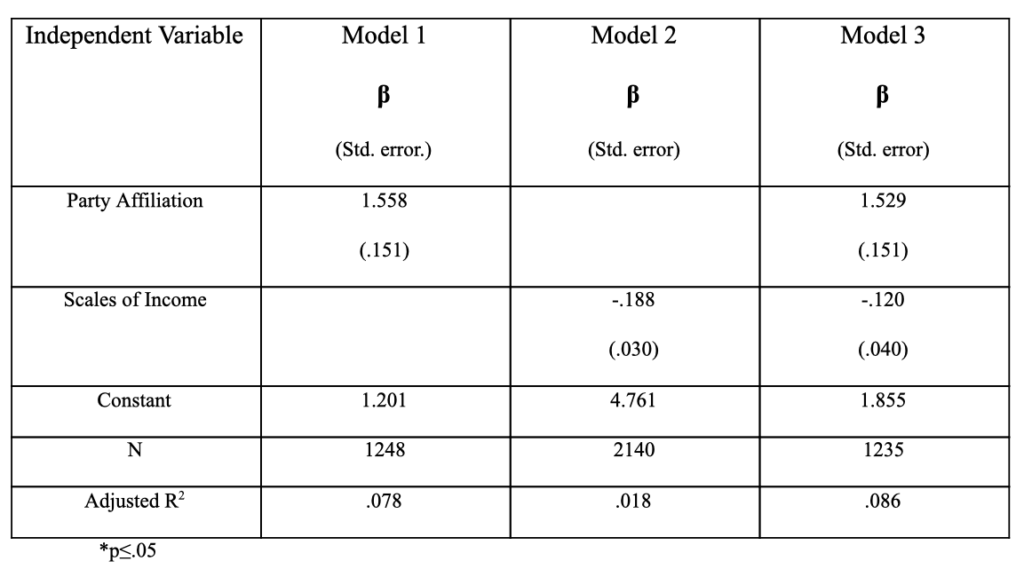

This table shows how the independent variables correlate with the dependent variable. Here, party affiliation appeared to have a more significant impact on an individual’s views about the importance of reducing income inequality. Party affiliation has a positive correlation coefficient which suggests that there is a positive correlation between democratic party affiliation and one’s views on the importance of reducing income inequality, this finding confirms the hypothesis that if an individual is a democrat, they are more likely to view reducing income inequality as important. The correlation has a magnitude of 1.529 which can be considered a sizable correlation with significance because of its distance from zero, this result also has a p-value of .000. This is a statistically significant positive correlation between democratic party affiliation and views on the importance of reducing income inequality. However, this variable only has an adjusted R2 value of .078, which suggests part affiliation only accounts for 7.8% of the variation in views towards income inequality. This implies there are other variables that can determine one’s view towards reducing income inequality. Due to the results of a 1.529 correlation coefficient with a p-value of .000, I reject the null hypothesis (H01).

On the other hand, the measure of scales of income is not as promising. The variable has a negative correlation coefficient that indicates as an individual’s income increases their view about the importance of reducing income inequality decreases. This result does support my second hypothesis. However, this variation seems to be much less significant than party affiliation. Income scale has a correlation coefficient of -.120 and a standard error of .040, this measurement is very close to zero which indicates a weak statistical significance in the correlation between higher income and lower importance placed on reducing income inequality. I would also like to point out this variable did have a p-value of .003, which is still a low p-value, however it is a higher p-value than party affiliation which indicates it is even less statistically significant than party affiliation. The adjusted R2 value of this variable is .018, which suggests this could only account for 1.8% of the variation in the dependent variable. Due to these insignificant results I cannot reject the null hypothesis (H02).

These results suggest that party affiliation is significantly correlated with an individual’s views about the importance of reducing income inequality. As discussed earlier a person’s political party affiliation tells us that they support the party’s ideals and what they stand for. The democratic party in the U.S. is known to run for redistributive tax policy and strong social welfare programs for the disadvantaged, so it is logical to expect their members to think this way too and place a higher importance on reducing income inequality and expanding the middle class like the party does. Whereas, the republican party is abrasive toward redistributive tax policy and expanding social welfare programs for the poor and tout a more meritocratic principle that you can pull yourself out of poverty with hard work, and if you cannot, then that is your fault, think “pull yourself up by your bootstraps”. Therefore, it is again logical to expect republican party members to also have these viewpoints and therefore be more tolerant of current income inequality and would not view working to reduce it as a very important issue. Individuals who affiliate with the republican party are exposed to more inequality-legitimizing myths and meritocratic principles and this confirms the system-justification theory (Roex et al 2018, Zimmerman and Reyna 2013, Larsen 2016). On this basis I believe I can reject the null hypothesis and confirm the original one.

In the case of income level, the effect of one’s income on their views of the importance in reducing income inequality is not statistically significant, this was determined due to the small magnitude of the correlation, the very small R2 value, and the small increase in p-value. Therefore, we are unable to reject the null hypothesis that income level does not affect an individual’s views towards income inequality. This lack of statistical evidence could be explained by several reasons. The first could be the possibility of the scale of income being an unreliable indicator, maybe measuring income in scales does not allow for as much variation that is needed to observe this relationship. Another explanation could be that the sample does not accurately represent the research population. From the mean and standard deviation, we can infer that most respondents were participants who make a middle level of income, maybe there were not enough participants from the further ends of the income scale that would cause us to see this relationship more significantly. Lastly, the theory could just be incorrect. As discussed, before it has been shown that societies with strong meritocratic principles can legitimize inequality so much that even individuals disadvantaged by the structure support its existence due to the perception that it is a fair process. The U.S. has always had pretty strong meritocratic principles, the “American Dream” is just one example of that, the idea that anybody can get out of poverty and make it to the middle class if they just try hard enough. Therefore, we could be observing a confirmation of the system-justification theory rather than confirmation of the structural position or social identity theories.

In order to obtain qualitative evidence to support my theory and quantitative results, in a COVID-19 world, I posted on social media asking friends, family, acquaintances, co-workers, colleagues if they would like to participate in a semi-structured interview for a research study. I interviewed four people I thought were most representative of my research population. Common themes emerged during content analysis of interview responses. Those who scored higher on the importance of reducing income inequality also viewed themselves as further left in political ideology, and those who scored lower slid down the right of political ideology. Participant 1 scored reducing income inequality as a “10 because reducing the insane income gap is an important job that needs to be done.” I then asked this participant how long they had held this viewpoint and the response was “not until the age of 19-20 when I moved out of my parents house and started to discover my own beliefs about the world and politics, I started moving towards the left of the political scale.” This showed that this participant did not view reducing income inequality as important until they moved away from identifying as a republican and towards identifying as a democrat and even further left. This theme emerged again in the second participant. I asked participant 2 how they would score the importance of reducing income inequality on a scale of 1-10, this participant also scored a “10”. When I asked how long they had held this viewpoint and if they could identify any influences in their life that may have shaped this viewpoint the response was, “I did not view income inequality as a real issue until I started discovering my own political beliefs after high school and moved further left down the political spectrum.” These two findings that link individuals moving towards the left of the political spectrum and starting to view reducing income inequality as important is significant. These case studies help confirm the statistical results given before about the positive correlation between democratic party ideology and viewing the reduction of income inequality as important.

Conclusion

In this study we were able to reject one null hypothesis (H02) but not the other. We were able to find statistical and qualitative evidence that individuals who affiliate with the Democratic party are more likely to view reducing income inequality as important. The statistical tests showed a strong positive correlation between party affiliation and views on reducing income inequality and the illustrative case study helped support this theory. This finding is supportive of the system-justification theory that was mentioned earlier. However, we were unable to reject the null hypothesis that there is no correlation between higher income level and views on reducing income inequality due to the statistically insignificant magnitude and R2 value. I suspect this could be for many reasons including unreliable indicators, indicators not representative of the research population, or simply the theory was wrong. This could be indicative that the system-justification theory prevails in the case of income scale as well. Further research should investigate this relationship between meritocratic principles and inequality legitimization in the U.S.

References

Hanauer, Nick, et al. “America’s 1% Has Taken $50 Trillion From the Bottom 90%.” Time, Time, 14 Sept. 2020, time.com/5888024/50-trillion-income-inequality-america/

Hadler, Markus. “Why Do People Accept Different Income Ratios?” Acta Sociologica 48, no. 2 (2016): 131–54. https://doi.org/10.1177/0001699305053768.

Roex, Karlijn L.A, Huijts, Tim, and Sieben, Inge. “Attitudes Towards Income Inequality.” Acta Sociologica 62, no. 1 (2019): 47–63. https://doi.org/10.1177/0001699317748340.

Zimmerman, Jennifer L, and Christine Reyna. “The Meaning and Role of Ideology in System Justification and Resistance for High- and Low-Status People.” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 105, no. 1 (2013). https://doi.org/info:doi/

Brandt, Mark J. “Do the Disadvantaged Legitimize the Social System? A Large-Scale Test of the Status-Legitimacy Hypothesis.” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 104, no. 5 (2013): 765–85. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0031751.

Larsen, Christian Albrekt. “How Three Narratives of Modernity Justify Economic Inequality.” Acta Sociologica 59, no. 2 (2016): 93–111. https://doi.org/10.1177/0001699315622801

Osberg, Lars, and Smeeding, Timothy. ““Fair” Inequality? Attitudes Toward Pay Differentials: The United States in Comparative Perspective.” American Sociological Review 71, no. 3 (2016): 450–73. https://doi.org/10.1177/000312240607100305.

Tajfel, H, Turner, JC (1979) An integrative theory of intergroup conflict. In: Austin, WG, Worchel, E (eds) The Social Psychology of Intergroup Relations. Monterey, CA: Brooks/ Cole, pp.33–47.

Jost, J. T. (2001). Outgroup favoritism and the theory of system justification: A paradigm for investigating the effects of socioeconomic success on stereotype content. In G. B.Moskowitz (Ed.), Cognitive social psychology: The Princeton symposium on the legacy and future of social cognition (pp. 89–102). Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.

Also published on Medium.