By Dana Craig

Background: Defining Civil Asset Forfeiture

Civil asset forfeiture is a law enforcement practice that allows officers to seize money and property suspected of having ties to crime. Unlike its counterpart criminal forfeiture, civil forfeiture is an in rem proceeding against the property instead of its owner (“In rem”). Therefore, it does not require that the property’s owner be charged with a crime in order for the seizure to occur (Knepper et al. 5). To recover their seized property the owner must demonstrate to a court that the property was illegitimately taken. The complexity and cost of engaging in the legal processes necessary to challenge a seizure are often too great for innocent owners to attempt (ibid, 21).

After a forfeiture occurs, some or all of the seized assets become funds for the law enforcement departments that executed the seizures (ibid, 5). A 2019 study by economist Brian Kelly found that the ability to retain these funds sets up a profit incentive for police departments to engage in forfeiture—even when forfeiture did not appear to be a valuable crime-prevention tool. Kelly found that an increase in forfeiture did not correlate to an increase in crimes solved, but higher unemployment rates, and therefore local economic stress, did lead to an increase in forfeitures (14, 15). This suggests that police departments view civil forfeiture as a tool to gather revenue.

Recognizing this negative incentive, some states have tried to enact reforms to tamp down on law enforcement’s ability to profit from seizures. When faced with these reforms, however, state and local departments can turn to a loophole called federal equitable sharing. This practice allows them to evade state regulations by partnering with the federal government to execute forfeitures (Carpenter et al. 1). State and local departments can receive up to 80% of seized assets from these joint forfeitures back as department funds regardless of their states’ policies (ibid).

Originally imagined as a way for law enforcement to disrupt organized crime, significant evidence now points to the abuse of civil asset forfeiture at the expense of vulnerable populations (“Asset Forfeiture Program” 1; Knepper et al. 8). Reform is needed to remove the profit incentives that lead police to abuse asset forfeiture. As a first step, funds from asset forfeiture should support community-based nonprofit efforts rather than law enforcement.

The Issue: Profits Incentivize Abuse and Fail to Support Communities

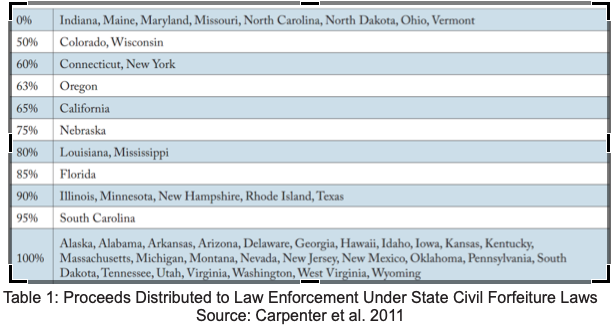

Civil asset forfeiture is a multibillion-dollar practice at both the state and federal levels. From 2002-2018 the federal government and the twenty states that most accurately track their civil forfeitures collectively seized $63 billion in currency and assets from individuals around the country (Knepper et al. 15). In most situations, states keep at least half of the assets seized in a forfeiture; only eight states bar law enforcement from profiting from forfeiture and 26 states allow law enforcement to retain all seized assets (Carpenter et al. 4).

Proponents of civil asset forfeiture laud it as a tool that allows law enforcement to give back to communities and the victims of crime. In its 2021 budget proposal, the DOJ highlights that since 2000 its Asset Forfeiture Program has given $7.2 billion back in restitution to victims (“Asset Forfeiture Program” 2). In addition to that money, however, from 2000-2019 the program also paid out $8.8 billion to state and local law enforcement agencies through the equitable sharing program—over $1.5 billion more than went to victims (Knepper et al. 47). Analyzing fifteen states from 2017-2019 reveals that forfeited funds at the state level are even less likely to end up supporting victims or community programs; each state spent 2% or less of their forfeiture proceeds on victim compensation and 12% or less on community programs (ibid, 54).

The DOJ describes civil asset forfeiture as a “powerful law enforcement tool for disrupting and dismantling well-funded criminal enterprise” (“Asset Forfeiture Program” 1). Across 21 states with available data, however, the median forfeiture averages only $1,276 (Knepper et al. 21). This suggests that the majority of forfeitures target individuals rather than large criminal enterprises (ibid). There is a problematic disparity, then, between the stated vision of civil forfeiture as a tool to combat organized crime and its lived use as a profit-incentivized policy that allows law enforcement to take money from individuals without charging them with a crime.

The small size of these civil forfeitures also makes them difficult for property owners to contest in court. The cost of hiring a lawyer to navigate the complex process of fighting a forfeiture often exceeds the amount of money seized (Knepper et al. 21). The obstacles property owners must face to contest a civil forfeiture are so onerous that only about 22% of forfeitures are ever challenged (ibid). As a result, police are often able to forfeit property without pushback, which serves only to strengthen the profit incentive that leads to the abuse of asset forfeiture.

Suggested Reform: Break the Profit Incentive

As a key first step in ending the abuse of civil asset forfeiture states should enact the following changes:

- Prevent law enforcement from using forfeited assets as department funds.

- Instead, reroute these assets to community programs.

- Mandate that all state and local police departments keep and make public detailed records of their participation in the federal equitable sharing program.

The current system of civil asset forfeiture in most states creates a profit incentive that invites law enforcement to view civil asset forfeiture as a source of revenue rather than a crime prevention tool. To prevent abuse, police cannot continue to use seized assets as department funds. Instead, legitimately seized assets at the local and state level should go to fund community programs.

A 2017 study by sociologists at New York University found that an increase in non-profit organizations in cities correlates to substantial drops in homicide rates, violent crime rates, and property crime rates (Sharkey et al. 1215). In a similar vein, a 2016 study done by the National Bureau of Economic Research found that increasing access to local substance abuse centers caused reductions in both violent and financially-motivated crime (Doleac). Supporting community-based non-profits and programs like food pantries, job training, affordable housing initiatives, and addiction rehabilitation works to reduce the amount of inequality, insecurity, poverty, and addiction in a community—all potential contributing factors to crime.

By rerouting the funds of legitimate asset forfeiture to community programs, the profit incentive for law enforcement to view asset forfeiture as a source of department revenue is broken but the ultimate goal of supporting safe and healthy communities remains intact. Opponents of this reform may argue that law enforcement departments need the funding from forfeitures to do their duties (“Attorney General Sessions”). However, investment in communities creates a cyclical solution to that issue: by supporting non-profits, crime rates fall and the burden placed on law enforcement decreases. Additionally, arguing that police departments need forfeiture funds to operate admits the presence of a profit incentive that encourages police to see forfeiture as a revenue builder. The stated goal of civil asset forfeiture is not to fund police, but rather to “deter criminal activity”—rerouting forfeited assets to community programs allows for this stated goal to persist (“Asset Forfeiture Program” 2).

In 2018 the state of Wisconsin enacted significant asset forfeiture reform within this model. Under 2017 Senate Bill 61, Wisconsin law enforcement cannot retain more than 50% of the funds collected from civil asset forfeitures, the funds they do retain must go toward forfeiture-related expenses, and all remaining assets must be deposited in the state’s school fund (Wisconsin State Legislature). With this change, Wisconsin broke the civil asset forfeiture profit incentive and instead rerouted funds to support the education, and opportunity, of the state’s children. Wisconsin offers a blueprint by which other states can model their reform efforts.

Bipartisan support for the reform of civil asset forfeiture is growing. Since 2014 a bipartisan group of lawmakers at the federal level have pushed for the Fifth Amendment Integrity Restoration Act (FAIR Act). This legislation would eliminate the federal equitable sharing program and raise the burden of proof necessary for federal law enforcement to forfeit property, but it has yet to pass (“Senators Paul, King, Crapo, and Lee”). In another show of bipartisan support for reform, the Supreme Court unanimously ruled in its 2019 case Timbs v. Indiana that the Eighth Amendment’s excessive fines clause does apply to the states and specifically to the practice of asset forfeiture. The Court found that forfeiting a person’s assets is synonymous with issuing them a fine, and as such under the eighth amendment forfeitures cannot be disproportionate to the seriousness of a person’s alleged offense (“Timbs v. Indiana”).

Unfortunately, reform efforts still face significant pushback from organized law enforcement opposition (Knepper et al. 56). While just a first step, ending asset forfeiture’s profit incentive by rerouting forfeited funds to community programs offers a way to combat this opposition because the proposed policy keeps civil asset forfeiture intact for situations when it is legitimately necessary to interrupt organized criminal enterprise. Opposition cannot argue, then, that law enforcement is using a valuable tool. Instead, the tool is modified to disincentivize the abuse of asset forfeiture. As an initial move this change will build momentum to substantial next steps.

Key in this solution is a mandate that all state and local law enforcement departments begin to immediately document and make public the scale of their participation in the federal equitable sharing program. State tracking of civil forfeitures is inconsistent and incomplete across the country (Knepper et al. 11). States should move to track the size of all asset forfeitures, the types of property seized, and what happened to the funds collected from forfeitures conducted at both the state level and through equitable sharing (ibid). These reports must be made easily accessible to the public, especially in the case of equitable sharing. Equitable sharing only serves as a loophole to allow state and local police departments to subvert state law (Carpenter et al. 6). To build support for the elimination of this program, the presence and size of this loophole must become clear to elected officials and their constituents.

Breaking the profit incentive for police to abuse forfeiture is the first and most essential step in civil forfeiture reform, but it is only the beginning. Future policy changes should include the elimination of federal equitable sharing and should strengthen the burden of proof required for law enforcement to seize property to “proof beyond a reasonable doubt” in all cases. This proposal offers a unified starting point from which all states can begin to enact substantial change to end the abuse of civil asset forfeiture.

Bibiliography

“Attorney General Sessions Issues Policy and Guidelines on Federal Adoptions of Assets Seized by State or Local Law Enforcement.” Department of Justice, United States Government, 19 July 2017, www.justice.gov/opa/pr/attorney-general-sessions-issues-policy-and-guidelines-federal-adoptions-assets-seized-state.

Carpenter, Dick M. et al. “Inequitable Justice: How Federal ‘Equitable Sharing’ Encourages Local Police and Prosecutors to Evade State Civil Forfeiture Law for Financial Gain.” Institute for Justice. 2011. https://ij.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/03/inequitable_justice-mass-forfeiture.pdf.

Doleac, Jennifer L. “New Evidence That Access to Health Care Reduces Crime.” The Brookings Institution, The Brookings Institution, 3 Jan. 2018, www.brookings.edu/blog/up-front/2018/01/03/new-evidence-that-access-to-health-care-reduces-crime/.

“In rem.” Merriam-Webster.com Dictionary, Merriam-Webster, https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/in%20rem. Accessed 23 Mar. 2021.

Knepper, Lisa et al. “Policing for Profit: The Abuse of Civil Asset Forfeiture.” Institute for Justice. 3rd ed. 2020. https://ij.org/wp-content/themes/ijorg/images/pfp3/policing-for-profit-3-web.pdf.

Kelly, Brian D. “Fighting Crime or Raising Revenue? Testing Opposing Views of Forfeiture.” Institute for Justice. 2019. https://ij.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/06/Fighting-Crime-or-Raising-Revenue.pdf.

“Senators Paul, King, Crapo, and Lee Reintroduce FAIR Act to Reform Civil Asset Forfeiture Process, Protect Innocent Americans.” Rand Paul, U.S. Senator For Kentucky, Office of Senator Rand Paul, 25 June 2020, www.paul.senate.gov/news/senators-paul-king-crapo-and-lee-reintroduce-fair-act-reform-civil-asset-forfeiture-process.

Sharkey, Patrick et al. “Community and the Crime Decline: The Causal Effect of Local Nonprofits on Violent Crime.” American Sociological Review, vol. 82, no. 6, 2017, pp. 1214-1240. https://journals.sagepub.com/eprint/VThwp5JSFz7eNKF5GkxW/full.

“Timbs v. Indiana.” Oyez, https://www.oyez.org/cases/2018/17-1091. Accessed 23 Mar. 2021.

United States, Department of Justice. Asset Forfeiture Program FY 2021 Performance Budget Congressional Justification. Web. 2020. https://www.justice.gov/doj/page/file/1246261/download.

Wisconsin State, Legislature. Senate Bill 61. Wisconsin State Legislature, 3 April 2017, https://docs.legis.wisconsin.gov/2017/proposals/reg/sen/bill/sb61.